Culture and biodiversity in Colombian coins and banknotes

From exotic birds to famous characters, our banknotes tell stories that will surprise you. Here, we tell you everything hidden behind our Colombian currency.

In Colombia, we are proud of who we are. That’s why we wanted each of our bills and coins to tell a story: the story of some of our paradise-like places and the fruits of our land, or that of fellow Colombians who, through their actions and dedication, have elevated the name of our country. While our biodiversity has always been featured on some of our bills, since 2012 it has taken center stage.

So much so that we now see, up close and in great detail, some stunning panoramas of the incredible natural wealth of our country. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves—what really grabs our attention is learning everything we can about the people and landscapes featured on our coins and bills. You’re sure to discover thousands of fascinating details that will amaze you!

The Cocora Valley and Carlos Lleras Restrepo, united by the one hundred thousand peso bill

Photo courtesy of Banco de la República.

The one hundred thousand peso bill, the highest denomination in our paper currency, tells two stories. The first one is about the Cocora Valley, named in honor of a Quimbaya princess whose name in Spanish would translate as Star of the Water, and which is one of the emblematic places of the Colombian Western Andes. Here, where the mist touches the sky and blends with the green grass, grows one of Colombia’s representative plants: the wax palm, that towering marvel that admires from above the vastness and beauty of the cloud forest landscape in Los Nevados National Park. With its height of over 70 meters, the palm is one of Colombia’s most majestic native natural wonders. It’s no surprise it was named the national tree of our country!

Featured on the bill is a wax harvester, one of the many who, in the early days of our nation, used this palm as a source for producing resins and oils. Alongside, as it couldn’t be otherwise, rests a poem by one of the masters of national literature: Luis Vidales.

The poet, born in Calarcá, knew the palm and its splendor well. That’s why he didn’t hesitate to dedicate a few verses to it: “To the palm of Quindío I once told my dream. It was the palm, it was, it was the wax palm, the palm tree, the palm of my dream. A rocket that rises to the sky and bursts into stars. And when the winds pass, the palm becomes a river... Hear the sound of the air, the river..., the palm of my child. Here I keep it, pressed close, here in my chest, on the left side of the soul where I carry Quindío.”

Photo courtesy of Shutterstock.

The second story told by this bill is that of Carlos Lleras Restrepo, former president of Colombia during the term from 1966 to 1970. His progressive and liberal government led reforms that still positively impact Colombian life today. On his left side, complementing the majestic Cocora Valley on the front, appears another inhabitant of this natural paradise: the barranquero bird, or momot, as it was called in an indigenous dialect. This beautiful traveler of Colombian skies stands out for its multicolored plumage and a striking blue and black crest that contrasts with its reddish eyes.

Photo courtesy of Birdscolombia.com

Alongside them, this side of the bill features a Sietecueros flower, a species native to our territory. Thanks to its beautiful colors and resistance to various climates, it is a common sight in many gardens and native forests across our country.

Photo courtesy of Wikipedia.

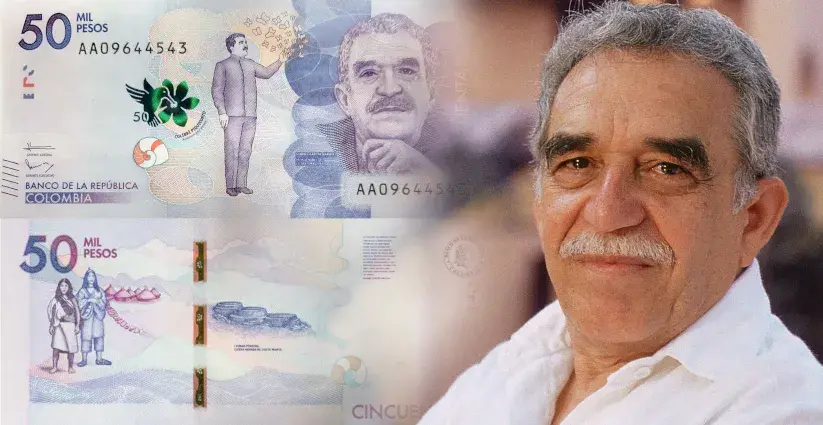

García Márquez and a soaring imagination, featured on the fifty thousand peso bill

The fifty thousand peso bill, the second most valuable in our country, tells the story of the life and work of Gabriel García Márquez, or “Gabo,” as we fondly remember him. There we see him, with his penetrating and intelligent gaze, captured for remembrance. Next to him rests a full-body sketch of the writer watching his eternal yellow butterflies fly up into the sky so that, alongside the short-billed hummingbird, it becomes clear that Colombia’s literary imagination knows no bounds.

Photo courtesy of Banco de la República.

Beneath the hummingbird lies a burgao sea snail, one of the exotic creatures that inhabit our land. This little animal, increasingly rare to see, is one of those beings that evoke the incredible natural wealth of Colombia, the same that amazed our ancestors from “Teyuna” or Ciudad Perdida, honored on the back of the bill. There, two Tairona Indigenous people pose in a drawing beside their homes, surrounded by the vast sacred mountains of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta. In the background, from afar, emerges the prose of García Márquez—especially his speech on The Solitude of Latin America.

The Zenú heritage and Alfonso López Michelsen, protagonists of the twenty thousand peso bill

The twenty thousand peso bill reminds us of the greatness of our Indigenous peoples and their timeless wisdom. Among their achievements was “taming” and adapting nature in order to coexist with other animals—without danger, without fear. This is evident when we observe the hydraulic system built in La Mojana, that region where the river delta was engineered by the Zenú tribe to prevent flooding. Because of this, the savanna would not be as we know it today—nor would it be as habitable—if the Zenú people had not conceived such a feat of engineering.

Photo courtesy of Banco de la República.

Accompanying the Zenú wisdom, on the same side of the bill is a farmer carrying caña flecha, a hallmark of the region. We can all guess what he’ll make with it: a beautiful sombrero vueltiao, whose woven strands embody Colombia’s incredible artisanal tradition. Benjamín Puche, a historian of the Zenú tradition and its legacy, writes in his poem—inscribed in the upper right corner of this side of the bill—how “fingers braid with rhythm a spring of stars.” The same stars that stir the soul every time we wear a sombrero vueltiao.

On the front we find Alfonso López Michelsen, president of Colombia from 1974 to 1978, who was a member of the Liberal Party. Next to him rests a sugar apple, that delicious fruit from our land that brings joy to the heart with just a single bite. Below it, once again, a Zenú ear ornament is honored.

Photo courtesy of Banco de la República.

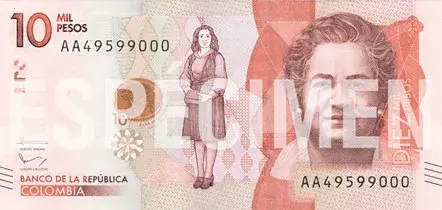

Virginia Gutiérrez de Pineda and the Amazonian legacy, depicted on the ten thousand peso bill

The ten thousand peso bill honors the achievements of one of the women who shaped our history: Virginia Gutiérrez de Pineda, a pioneer in anthropology and sociology who, thanks to her book Family and Culture in Colombia, paved the way for continued studies on family and society in Latin America. For her contributions and commitment to Colombian women—those who, as she notes in her prologue (quoted on the back of the bill), “share and multiply bread” with all their loved ones—Virginia Gutiérrez stands as a symbol of women's empowerment and their accomplishments.

Photo courtesy of Banco de la República.

To the left of her full-body portrait rests the tree frog (Hypsiboas granosus), one of the colorful and charming creatures of our land that highlights Colombia’s incredible biodiversity. Below it appears the flower of the Victoria Regia, a native water lily from our Colombian Orinoquía-Amazonía.

Photo courtesy of Shutterstock.

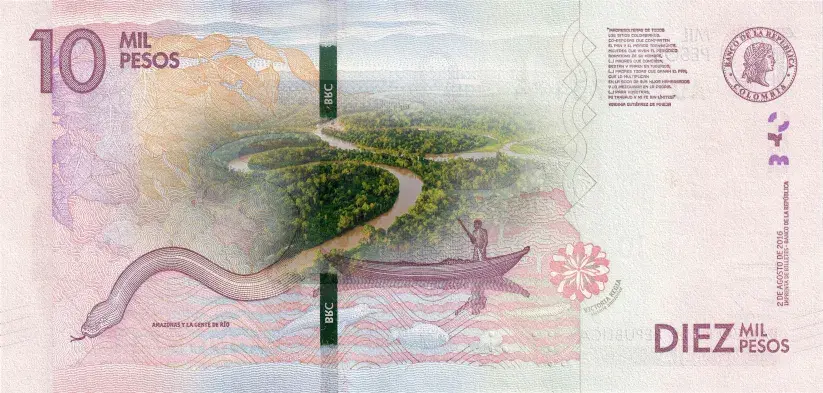

On the back of the bill, the majestic Amazon rainforest and its imposing creatures are illustrated in more detail. Since many of its mysteries remain hidden, we honor this paradise of life through what we’ve been able to perceive from our human vulnerability.

Photo courtesy of Shutterstock.

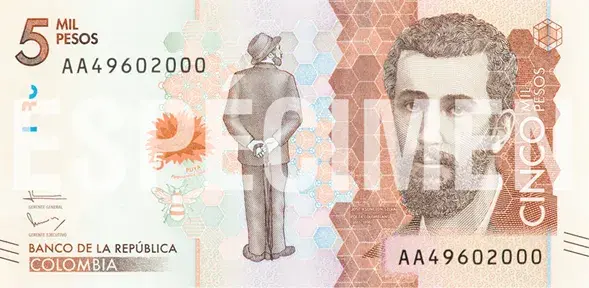

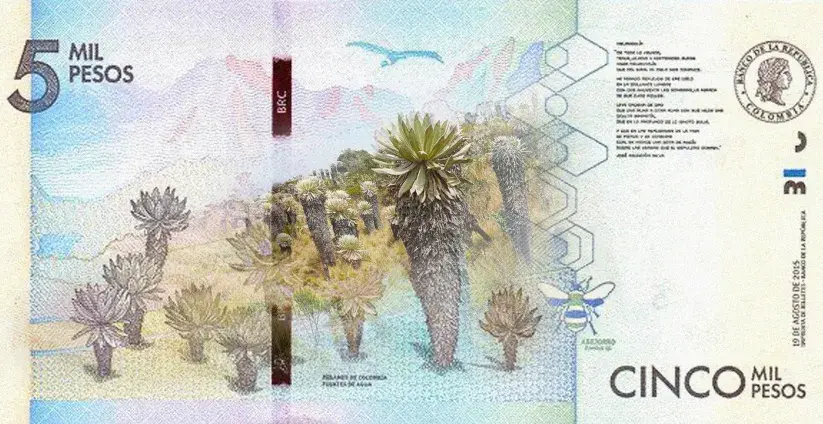

José Asunción Silva and the páramo landscape feature on the five thousand peso bill

Silva lived a thousand and one lives: the ones captured in his verses, those lost with the shipwreck on his return to Colombia, and those we remember by heart; the ones that recalled each of his journeys, the ones that saw more than one business fail in Bogotá, and those that ultimately colored the words of what would become the greatest poet of the savanna. On this bill, he is remembered in his lineage and youth alongside one of his most beloved poems: Melancholy, printed on the reverse.

Photo courtesy of Shutterstock.

Next to the poet’s full-body portrait, a bumblebee and a puya plant (Paepalanthus columbensis) appear—just two of the many natural wonders that awe those who visit our páramos for adventure, hiking, or birdwatching.

Photo courtesy of Shutterstock.

On the reverse side of the bill are drawings of the beautiful Andean mountains and several frailejones, watched over by an Andean condor, guardian of our skies. Once again, the bumblebee appears to remind us of the thousands of native species—small and large—that call these highlands home.

Photo courtesy of Shutterstock.

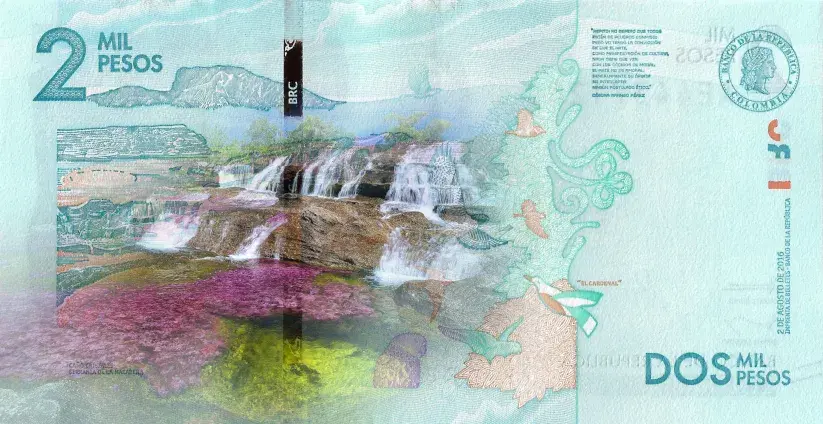

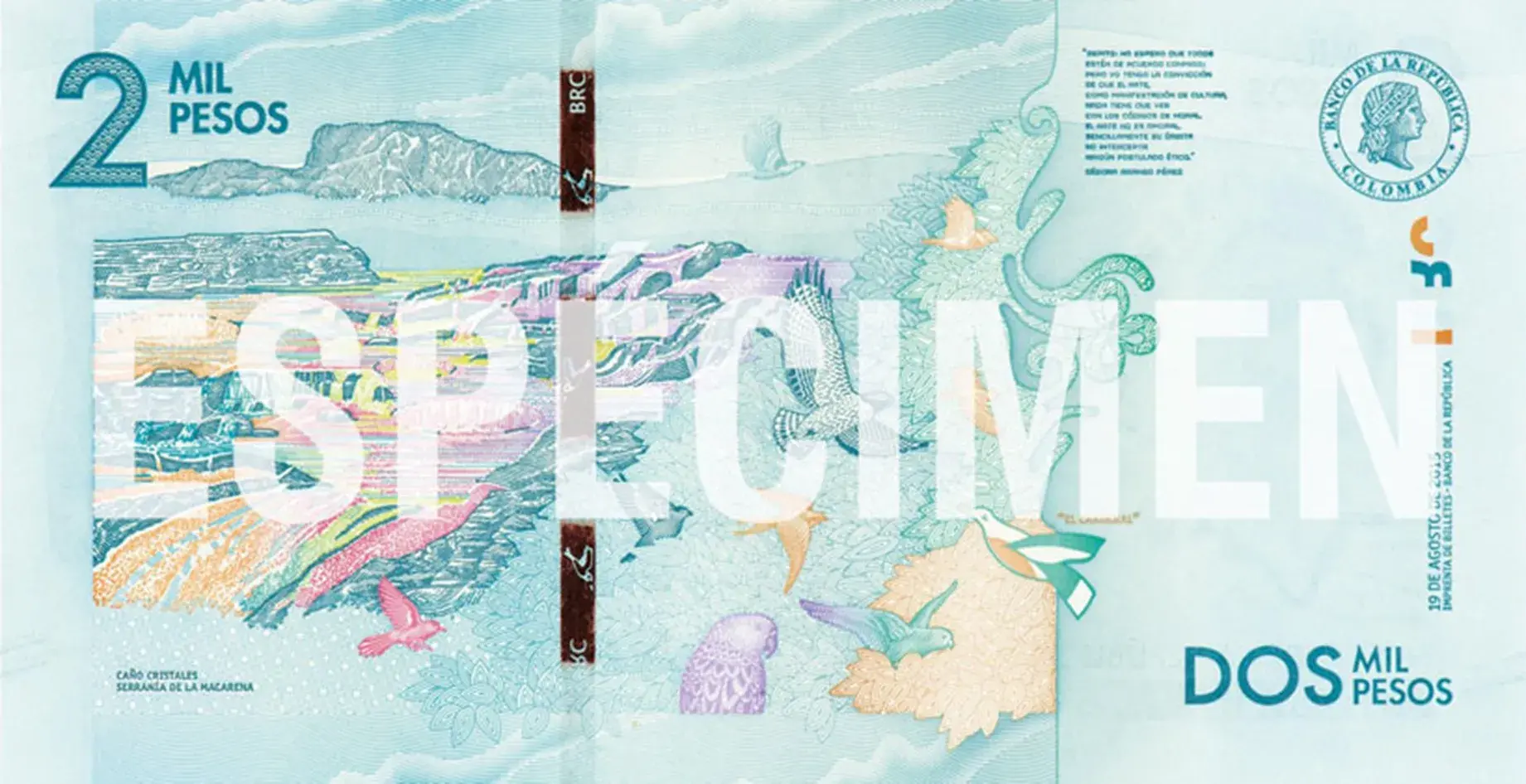

Débora Arango and Caño Cristales, protagonists of the two thousand peso bill

Débora Arango broke every mold of what was expected of a Colombian artist in her time: she was the first to paint female nudes and one of the pioneers of social and critical art in our country. For this and more, her smiling face appears on the front of this bill, alongside the little red bird in El recreo-las monjas y el cardenal, one of her most iconic works.

Photo courtesy of the Botero Museum collection.

Beside her, accompanying the little bird from her painting, are depictions of some leaves and the fruit of the milk tree (Brosimum utile). This tree, native to our Colombian Amazon-Orinoquía, reminds us of the rich nourishment of our soil, the same that allows thousands of plant and animal species to thrive better here than anywhere else in the world.

Photo courtesy of Banco de la República.

On the back of the bill, Caño Cristales takes center stage—the incredible five-colored river that amazes all who see it. Alongside it, several animals from the region appear: parrots and other birds soar over the Serranía de la Macarena, one of the paradisiacal places in this region. The red bird from Débora Arango’s painting flies through the clouds as well.

Photo courtesy of Banco de la República.

Our Water Wealth: The Theme of the 1,000-Peso Coin

The 1,000-peso coin reminds us of the thousands of rivers and water sources that Colombia is home to. On the front, waves mimic the movement of water, beneath the motto “care for the water.” Much of our history was built alongside rivers, in the shade of old breezy patios, following the wake of steamships that still navigate the Magdalena River. This coin invites us to protect this vital liquid and the paths it travels.

On the back, a loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta) is engraved, one of the many marine species that choose the beauty and calm of our beaches in Colombia’s Greater Caribbean and Pacific coasts to nest and reproduce.

Photo courtesy of colombia.inaturalist.org

Next to it, the call to care for water and life can once again be read. In fact, the word “AGUA” (WATER), in all caps, is repeated seven times among the ripples caused by the turtle's swim.

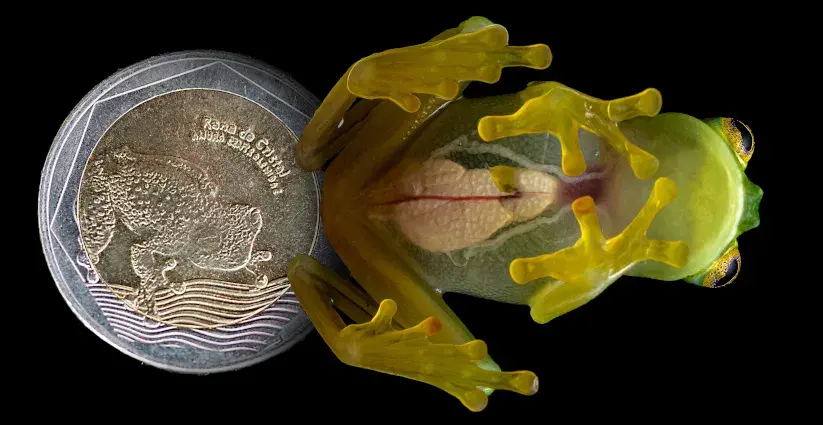

The Glass Frog and the Biodiversity of Our Andes: Themes of the 500-Peso Coin

After some subtle nods to the movement of water on the front side, the coin’s reverse features the animal that hides nothing, revealing itself in all its beauty and vulnerability: the glass frog. This tiny creature is known for its translucent skin—its internal organs are visible through its chest. In Colombia, it can be seen hopping between the crevices and branches of trees in our humid forests. A true gem!

Photo courtesy of National Geographic.

Our Flora and Fauna Celebrated on the 200, 100, and 50-Peso Coins

The 200-, 100-, and 50-peso coins follow the same path as the 500- and 1,000-peso coins. Once again, they feature some of the most charismatic species of our natural world: the spectacled bear, the frailejón, and the scarlet macaw.

Photo courtesy of misanimales.com.

The scarlet macaw (Ara macao) is the special guest on the 200-peso coin. This bird, a symbol of Latin America, displays in its feathers the colors of our national flag. Vivid and majestic, the macaw soars across the Colombian jungle skies, dazzling those who gaze upward from the forest floor. And while thousands of incredible species nest in the clouds, on our land there is a plant worth its weight in gold—or rather, in water: the frailejón. As the guardian of our páramos, it rightfully earned its place on our national currency.

Photo courtesy of the Bank of the Republic.

Just like the frailejón, Colombia sought to honor the majesty and splendor of the Andean landscape through one of its most beloved and gentle inhabitants: the spectacled bear. This bear can be seen playing, eating plants, or hunting peacefully in our páramos and humid forests. Thanks to conservation efforts by environmental authorities, many other species also benefit from its protection.

Photo courtesy of Shutterstock.

In addition to honoring this noble and beautiful forest dweller, the 50-peso coin calls on us to protect and observe it from a distance, without interfering with its ecosystem in any way. These coins and bills emphasize that the greatness of our country is not exclusive to humans but has been built hand in hand with, and in harmony with, other living beings.

These are some facts about the characters and the incredible biodiversity represented on our Colombian coins. Because here in Colombia, we don’t just use “paper money”—our currency carries stories and natural wealth we’re proud of. That’s why we chose to honor these things on the objects that pass from hand to hand each day. So that, whenever we have the chance, we can reconnect with a part of ourselves told through every coin and bill.

These are just some of the stories behind the characters and ecosystems featured on our Colombian currency. They’re the meanings behind the imagery that travels from hand to hand every day. And in turn, they are part of our history, culture, and biodiversity—a reflection of Colombia’s beauty and identity. Don’t miss out on discovering all that our country has to offer—explore it here.

Welcome, you are in

Welcome, you are in